By Natalie Jayne Clark

There are three bits of tangible evidence remaining to me that I was indeed a kid with cancer: two photographs where I am modelling a look that can only be described as ‘Uncle Fester’; a stack of medical records; and my diaries – consisting mostly of short entries which detail my hospital visits, the effects of the chemo, and poems I wrote.

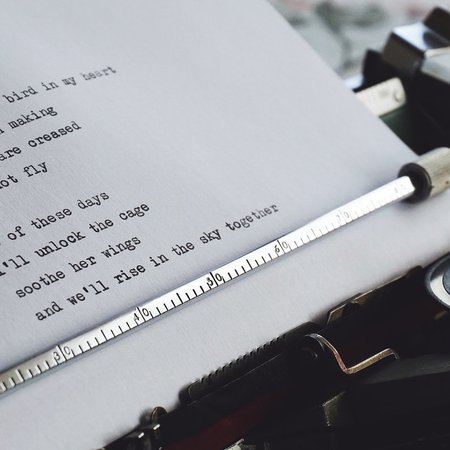

The poetry written in that period of my life was never meant to be read by anyone – I didn’t even intend a future me to see it. It was the writing of it that was important – to take the thoughts away from my brain and see them on the page, to channel my feelings into letters and words, to see them moved around and summed up on the page. Each finished poem was a release of pain at the time – an acknowledgement to myself that it did hurt, it wasn’t fair, and I was listening.

Over the years since, I have written smatters of poetry but I’ve not needed it again the same as I did when I was ill – until this last year. A good friend from school and I began calling each other weekly to give each other prompts and comment on our resulting poetry as a way to stay in touch and be creative. Then, we joined The Scribbler’s Union, a writing group led by Kevin P. Gilday and we’ve just blossomed. I write poetry so regularly now that I have no idea what I did with my random thoughts, my dark moments, and my intense feelings before.

For me, a lot of the magic of the form is that a poem can be conceived, written and re-written, edited and complete in just one morning or a single train journey. Poetry spills out urgently in ways other writing doesn’t. Poetry is not restrained by style or structure or even by the audience’s ability to read it. If you want to write disconnected words all over the page then you rightly should. They are your words and they do not need stage directions to be followed by actors or require punctuation to aid clarity or paragraphs to allow the reader’s eyes to gloss smoothly over to permit absorption into a story world. The performance of poetry can be sibilant whispers or staccato shouts, it can be still or gyrating with gestures, it can be a sedate literary reading or a dramatic monologue.

It’s not just writing and performing poetry that has provided me with solace this past year. The 2020 Paisley Book Festival took place only a month before our first national lockdown and I feel like I’ve been dining out on those live events ever since; the ones that stand out the clearest to me now are the poetry ones: they reignited an excitement for poetry that had been dulled over the years. Since then, I have been watching and reading so much poetry.

Throughout the various levels of lockdown, I have struggled to read at my usual pace, and I am still lamenting a part of me there that feels lost, but poetry has helped me to keep reading. I used to find poetry tricky to read – where are the complex characters, suspenseful narratives and beautiful journeys, I thought – but now I appreciate that poetry contains all of these things. Its form actually cuts through my severely depleted attention span. There’s nothing like poetry to instantly create an atmosphere or an emotion. A poem represents a slice of a poet; a poem is a facet of them and their experiences. When I read or hear poetry, I take on bits of them. Lines ring around my head for days afterwards and my self-awareness and empathy are heightened.

Through writing poetry, we can see our thoughts distilled into tight lines – we can observe the words from all angles in the process of selecting exactly the right few. Through performing poetry, we swell our words with emotion and experiment with our voices. Through reading and listening to poetry, we can sharply feel what the poets feel and inhale their message in less time than it takes to listen to a song. Through poetry, we share the human experience.